Meister Ihres Faches

Im Laufe der Jahre haben wir in elf verschiedenen Dörfern in fünf Ländern enge Arbeitsbeziehungen mit Kunsthandwerkern und ihren Familien entwickelt. Wir empfinden es als eine große Ehre, dass die Kunsthandwerker unsere Partnerschaft gleichermaßen schätzen und wir ihre traditionellen handgefertigten Textilien in funktionalen Taschen und Rucksacken weltweit anbieten können.

Die Kunsthandwerker sind echte Meister ihres Handwerks und vieles mehr! Sie sind Eltern, Gemeindeführer und Unternehmer in ihrem eigenen Recht.

Viele von ihnen sind ausgezogen und sind in ihre Dörfer zurückgekehrt, um mit ihren Familie zu leben und zu weben. Sie sind geschäftlich und technologisch versiert, sie sind nicht auf der Suche nach Almosen. Sie suchen nach einem langfristigen Geschäft!

Unser gemeinsames Ziel ist es, ihre Kunst einem großen Publikum zu zeigen um somit ihre eigene Kultur und Techniken zu bewahren.

Die Kultur und der persönliche Ausdruck der Kunsthandwerker sind buchstäblich in den jeweiligen Stoff gewebt. Die Nachfrage nach ihrer Arbeit ist ein direktes Ergebnis aus deiner Entscheidung, eine Ethnotek-Tasche zu kaufen.

Der Kauf eines handgefertigten Stoffes finanziert die Fortsetzung dieses Handwerks und unterstützt die Kultur, die in ihn eingewebt ist. Positive soziale Auswirkungen und kulturelle Erhaltung durch direkten Handel mit Meistern ihres Faches stehen im Mittelpunkt von Ethnotek.

Unsere handgefertigten Stoffe aus Ghana werden gedruckt von Kunsthandwerkern um den Künstler Reiss Boafo aus Accra, Ghana. Ein handgroßer Block aus Holz wird geschliffen, bis er eine perfekte flache Oberfläche hat. Dann werden die kompliziert entworfenen Motive aus der ghanaischen Kultur in den Block mit Messern und Meißeln geschnitzt und die Bahnen aus Baumwolle gestempelt.

Sowohl Stempel-Batik als auch Tie-Dye-Batik (Knoten-Batik) wurden in den 1960er Jahren ausgehend von Südostasien in Ghana eingeführt. Batiken waren aufgrund der leuchtenden Farben von Mitte der 1960er bis Ende der 1970er Jahre schwer in Mode in Ghana. Die Beliebtheit dieses Gewebes ging in den 80er Jahren aus verschiedenen Gründen erheblich zurück, vor allem aber, da sich eine Vorliebe für die günstigeren, industriell gefertigten Import-Textilien durchsetzte. Batiken haben jedoch in den letzten Jahren eine Wiederbelebung erfahren.

Frühe afrikanische Batiken beinhalteten viele Flecken und Spritzer auf den Entwürfen. Es ist auch üblich, bereits gefärbte Stoffe noch ein weiteres Mal zu batiken und die Stoffe mit anderen Stoffen zu vernähen. Andere Techniken sind direkte Malerei und Spritzen des Wachses auf den Stoff vor dem Auskochen. So entstanden über die Jahre eine einzigartige Handschrift und der afrikanische Batik-Style.

Das Kunsthandwerk der Batik ist für viele Bewohner aus ländlichen Gebieten ein Weg aus der Armut. Durch die geringen Startinvestitionen erstellen überwiegend Frauen in Heimarbeit schöne und farbenfrohe Designs für die lokalen und internationalen Märkte. Wir könnten nicht stolzer sein, ein Teil dieses Kunsthandwerkes zu sein.

Von der Wüste bis zu den Bergen, den Meeren bis zu den Vulkanen spannen sich die gewebten Stoffe schon seit Jahrhunderten. Die Motive sind verwurzelt in vielen Kulturen und sind so einzigartig wie die Kunsthandwerker, die sie weben. Es ist Zeit, die Menschen vorzustellen und die Geschichte der traditionellen Webkunst zu erzählen!

Die kleine Bergstadt Paxtoca (ausgesprochen Pashtoca) gerade außerhalb von Quetzaltenango, Guatemala, ist unsere Quelle für gewebte Maya-Textilien. Die Landwirtschaft ist immer noch die primäre Einnahmequelle der Bewohner (meist Mais und Äpfel), aber die Webkunst Ausdruck des Lebens und der Identität. Die einheimischen Frauen und einige der Männer aus älteren Generationen tragen weiterhin ihre traditionelle Maya-Kleidung, bekannt als Tipica.

Der Prozess beginnt mit dem Spinnen von Baumwollgarn in sorgfältig gemessene Abschnitte mit dem Namen "Cordeles", in welche dann eine größere Charge von Garn namens "Labores" gewoben wird.

Die ungefärbten Schnüre sind über einen Holzrahmen gestreckt und in mehrere einzelne Bündel getrennt. In diese Bündel wird dann ein Muster, das nur dem Kunsthandwerker bekannt ist, aus kleinen Knoten gebunden.

Nach dem Färben der Cordeles werden sie auf ein Rad geschleudert, das mehrere Spulen erzeugt, die dann in den Rechen geladen werden, der während des Webens verwendet wird, um den Abschluss zu definieren. Die "Kette" ist die lange vertikale Richtung des Garns, die den Großteil des Grundgewebes ausmacht.

Die Art des Webstuhls, der in Guatemala benutzt wird, wird "treadle loom" genannt. Dies beschreibt einen größeren, holzgerahmten Webstuhl. Der Rechen an der Vorderseite des Webstuhls füttert den Kettenfaden in den Kopf des Webstuhls, wo der Weber sitzt, um das Motiv und das Schiffchen zu führen. Unterhalb des Webstuhls wird der Stoff aufgerollt und so die Spannung gehalten.

Einer der wichtigsten Schritte im Webprozess ist eine Reihe von Auf- und Abwärtsbewegungen, die die Schichten des Stoffes voneinander trennen, damit das Schiffchen durchlaufen kann. Diese Bewegung definiert das Motiv und wird vom Fußpedal durch den Künstler unter dem Webstuhl betrieben. Der Prozess ist sehr rhythmisch und scheint fast einen eigenen Trommelschlag zu schaffen.

Am Ende werden das Motiv und die Farben magisch aufgedeckt. Obwohl wir den Prozess gut verstehen, ist es immer wieder ein kleines Wunder zu erleben, wie ein solcher Detailreichtum entsteht. Ausgehend von lediglich dem Garn und einem Bild in der Vorstellung des Künstlers, entstehen Muster von Maya-Menschen, -Tieren, -Symbolen und -Pflanzen auf den fertigen Textilien.

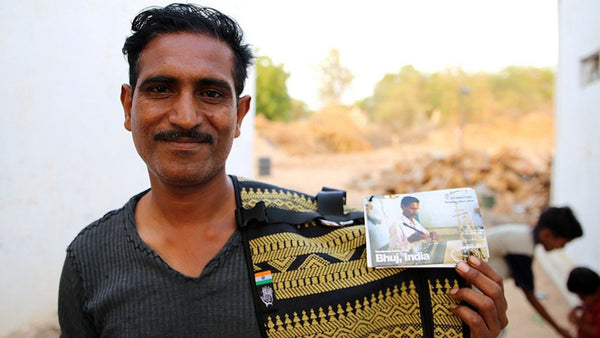

Jetzt reisen wir in die Region des Großen Rann von Kutch. Das Wort Kutch (ausgesprochen "katchh") kommt aus Kachwa, was in etwa "eine Schildkröte, die aus dem Meer gekommen ist“ bedeutet. Diese riesige Halbmond-Region gehört zum zweitgrößten Bezirk Indiens, Gujarat, und ist von dem Arabischen Meer im Westen und Pakistan im Norden begrenzt.

Archäologische Aufzeichnungen deuten darauf hin, dass diese Gegend bereits vor 30.000 Jahren von prähistorischen Menschen bevölkert wurde. Das heutige Kutch beherbergt 25 verschiedene ethnische Gruppen, die sich über mehr als hundert Dörfer verteilen. Zwei dieser ethnischen Gruppen, die Vankars und Rabaris, sind eng in die Ethnotek-Geschichte verwoben.

Das Weben in einer Grube (Pit-Looming) ist die Hauptform des Webens der Kunsthandwerker aus Kutch. Der Weber sitzt beim Pit-Loom-Webstuhl in einer Betongrube unter dem Webstuhl und arbeitet gleichzeitig mit Händen und Füßen.

Die Grube beherbergt auch die Schussschaufeln, die der Handwerker mit den Füßen betreibt. Gruben-Webstühle sind einfacher zu Hause zu integrieren, weil sie nicht so viel Platz wie ein Rahmen-Webstuhl benötigen und sie sind auch ein Weg, um in der Hitze der Wüste tagsüber arbeiten zu können.

Die Grubenwebmaschinen von Kutch benutzen ein manuelles Wurf-Schiffchen und ein handgespanntes Garn, das die Motiv-Stickerei einwebt. Das Weben auf einem solchen Webstuhl erfordert große Geschicklichkeit, Liebe zum Detail und Geduld. Das Ergebnis sind atemberaubende Kunstwerke mit tanzenden geometrischen Mustern. Es ist unmöglich, das authentische Aussehen und die besondere Haptik auf einer Maschine herzustellen.

Während es vor allem die Männer sind, die in Kutch die Webarbeiten machen, ist der Prozess eine kollektive Anstrengung, die die gesamte Familie einbezieht. Die Mütter, Ehefrauen und Schwestern bereiten das Garn zum Färben vor und erstellen Spulen aus Strängen des Garns.

Die beiden Zwillingsbrüder Sanjay und Suresh (20) haben sich dafür entschieden, im Dorf Kandherai zu bleiben, um das Familiengeschäft der Weberei weiterzuführen. Auf unseren Sourcing-Reisen sehen wir immer öfter, dass jüngere Generationen zunehmend demotiviert sind, traditionelles Handwerk weiterzuführen. Daher ist es erfrischend und inspirierend, diese beiden angehenden Meister zu sehen, die sich für das Weben entschieden haben. Für die Kunsthandwerker in Indien hat die Erhaltung ihrer traditionellen Webkultur eine hohe Priorität und sie sehen globalen Handel als eine nützliche Hilfe für diesen Zweck. Wir sind stolz und geehrt, uns hinter sie stellen zu können und diese Mission zu unterstützen.

Der Webmeister Premji (s.o.) ist seit vielen Jahren mit unserem Partner-Webmeister Shamji befreundet und war der erste Kunsthandwerker, der beauftragt wurde, Textilien für Ethnotek zu weben. Wir profitieren von seiner langjährigen Erfahrung im Weben. Er ist seit Beginn ein wichtiger Partner des indischen Ethnotek-Teams. Wir ehren Premji mit einem Portrait auf den Hangtags für unsere indischen Taschen und haben einen Rucksack nach ihm benannt.

Die handgefertigten Stoffe der Ethnotek Taschen aus Indonesien stammen aus den Händen der Kunsthandwerker aus Surakarta, Indonesien. Die aufwendigen Batiken aus gefärbter Baumwolle sind Kunstwerke und eine moderne Hommage an verschiedene sehr traditionelle Techniken, sowohl aus dem Batik-Design als auch aus der klassischen ostasiatischen Architektur.

Gewebtes Schilf, Palmenblätter und wilde Gräser waren ein multifunktionales Kernelement vieler Kulturen von Peru bis zu den Philippinen. Das Design für den Stoff des Musters Indonesia 6 entstand aus dieser klassischen Weberei, die in der indonesischen Architektur an Dächern und Wänden weit verbreitet ist, aber noch viel mehr in Fußmatten namens Tikar Pandan in Surakarta. Diese Matten werden jede Nacht in Warungs (kleine Straßencafés), wo sich die Menschen versammeln, um spät in der Nacht Snacks zu essen und Tee zu trinken, ausgerollt. Lasst uns einen Blick darauf werfen, wie die Batik im Surakarta-Style hergestellt wird!

Schritt 1: Es beginnt mit einer Zeichnung. Mit Bleistift und Pergamentpapier ergibt sich eine transparente Vorlage für die Stempel-Künstler. Für die Kunsthandwerker ist Batiken ist eine traditionelle Technik, um die geometrischen Entwürfe ihrer Vorfahren aufzuarbeiten.

Schritt 2: Die Kupfer-Stücke werden auf magische Weise in die Form gebogen, wie sie der Zeichnung des Künstlers entspricht. Es ist beeindruckend, wie präzise das Kupfer geformt wird. Die Kupferstreifen werden mit Zangen, Hämmern, Scheren, Hacken und Feilen bearbeitet – das ist echte Handwerkskunst!

Schritt 3: Der Künstler macht eine Qualitätskontrolle, um sicherzustellen, dass der Kupferstempel mit seiner Zeichnung übereinstimmt.

Schritt 4: Der überprüfte und gegebenenfalls nachjustierte Kupferstempel wandert in das Regal des Wachsstemplers.

Schritt 5: Hier dreht sich alles um Reduktion ... Der "Batik-Chef", der das genaue Rezept für das Batik-Wachs kennt, schmilzt das Wachs, so dass der Stempler das Wachs auf den Baumwollstoff auftragen kann.

Schritt 6: Der Stempler nimmt den Stempel des Kupferschmiedes und taucht diesen in das Wachs des Chefs ein. Der Stempel wird extrem sorgfältig auf das unberührte Baumwollgewebe gedrückt. Nun, da das Wachs aufgetragen wurde und in den Fasern der Baumwolle versickert ist, ist es Zeit für den nächsten Schritt.

Schritt 7: Der mit Wachs gestempelte Baumwollstoff wird in Farbstoff gebadet.

Schritt 8: Den gefärbten Stoff trocknen, Wachs auskochen, aufhängen zum Trocknen.

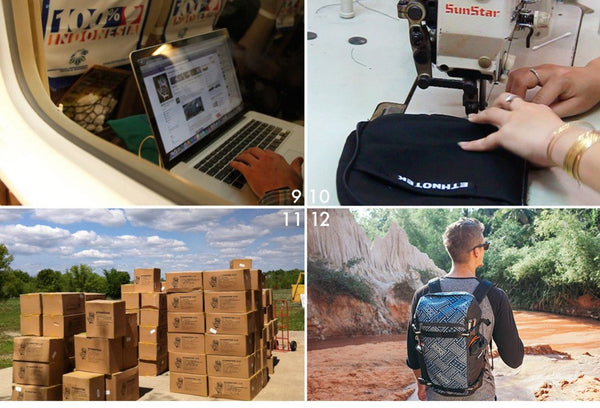

Schritt 9: Wir sammeln Kundenaufträge und platzieren dann bei den Kunsthandwerkern einen Großauftrag. Die Kunsthandwerker werden vorab bezahlt, so dass sie bereits während der Arbeit ein Auskommen haben.

Schritt 10: Sobald der Stoff in der Ethnotek-Manufaktur in Vietnam ankommt, wird er mit großer Liebe und Sorgfalt in fertige Ethnotek-Taschen eingenäht.

Schritt 11: Die neue Kollektion steht bereit, um an dich verschifft zu werden.

Schritt 12: Der Zyklus ist nun komplett. Wenn du eine Tasche mit diesen Stoffen kaufst, ist dies eine direkte Nachfrage nach der Kunst der Kunsthandwerker. Deine globale Nachfrage nach lokaler Handarbeit hilft, die Kultur der traditionellen Textilherstellung zu bewahren, die buchstäblich in jedes Stück gestempelt und gewebt wird. Du kannst deine Tasche dann mit Stolz tragen, im Bewusstsein um die Geschichte dahinter und die wundervollen Menschen, die diese von Hand gemacht haben.

Wir haben immer offene Landschaften, Schotterstraßen, unverfälschte Kultur, traditionelle Techniken, Handfertigungsprozesse und lebendige Farben geschätzt und uns mit ihnen verbunden gefühlt. Orte, die dies alles erfasst und damit zu unseren Lieblingsgebieten geworden sind, sind Sapa und Lai Chau im nördlichen Hochland von Vietnam.

Die Hmong Gemeinde lebt in einer Gegend eingebettet in der Hoàng-Liên-Son-Berglandschaft von Nordwest-Vietnam, mit Blick auf die terrassenförmig angelegten Reisfelder, die sich zwischen der Dien-Bien-Provinz im Osten bis hin zu Cao-Bang-Provinz im Norden erstreckt.

Die ethnische Gruppe der Hmong migrierte ursprünglich im 18. Jahrhundert aufgrund politischer Unruhen aus China nach Süden und suchte in Nordvietnam, Laos und Thailand nach mehr Ackerland. Die Hmong bilden die größte der 54 ethnischen Gruppen in Vietnam, die wiederum in zahlreiche Untergruppen wie die Schwarzen, Roten, Grünen, Weißen oder Blumen unterteilt werden, jeweils mit ihrem eigenen Dialekt, Glaubenssystem, kulturellen Bräuchen, Kleidern & handgefertigten Textilien.

Seit Jahrhunderten stellen Hmong-Frauen Kleider für ihre Familien von Hand her. Oft lernen sie dies schon, wenn sie sechs oder sieben Jahre alt sind. Eine Hmong-Frau webt und stickt ihr ganzes Leben lang, und die Schönheit und Intelligenz einer Frau wird an ihren Textil-Herstellungsfähigkeiten gemessen.

Mit nur einer Reisernte im Jahr verbringen die Frauen von Sapa und den umliegenden Dörfern ihre Tage mit Kunsthandwerk, plaudern beim Tee, während sie sticken, teilen eine Rolle Leinenfaser vom Markt oder sitzen mit Freunden zusammen, während sie ihre Fäden vorbereiten. Wenn es einen Faden gibt, der sich durch die Identität einer Hmong-Frau zieht, ist es ganz buchstäblich ihr Textil-Handwerk.

Die Hmong glauben, dass andere ihres Stammes sie auf Grund der Stoffe und des Stils der Stickereien, den sie tragen, erkennen können. Die starke Bindung zu ihrem Handwerk geht sogar in ihren spirituellen Glauben über. Wenn sie sterben, kleiden ihre Kinder sie in den entsprechenden Stoffen ihres Stammes an, damit ihre Vorfahren sie im Jenseits erkennen können.

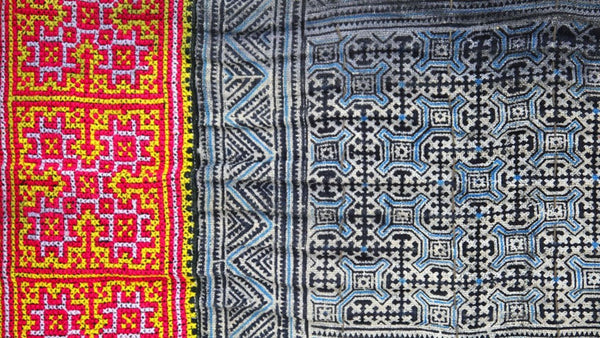

Im Hinblick darauf, sich auszudrücken, wird die Stickerei als eine der höchsten Formen der Kreativität in der Region verehrt. Es gibt unzählige Stickerei-Techniken, die von Künstlern auf der ganzen Welt angewandt werden, aber sie alle sind Variationen von drei grundlegenden Arten: Flach-Stich, Knoten-Stich, Schleif-Stich. Einige flache Stiche, wie Lauf-, Satin- und Kreuzstich, liegen auf der Oberfläche des Stoffes auf. Geknotete Stiche haben ein angehobenes oder verzierendes Muster auf der Oberfläche. Das klassische Beispiel eines verknüpften oder geschleiften Stiches ist ein Kettenstich, bei dem die erste Masche durch den nachfolgenden Stich gehalten wird.

Die leuchtenden Farben des Stickfadens kreuzen sich, um eine komplexe Reihe von Symbolen auf einem "Tuch mit Geschichten", genannt Pajntaub, zu kreieren, das oft eine Vielzahl von Themen abbildet, die auf der Mythologie oder Natur beruhen. Die häufigsten verwendeten Motive sind solche, die im Alltag gefunden werden, einschließlich stilisierte Darstellungen von Schnecken, Bergen, Hühnerfüßen, Widderhörnern, Gurkensamen, Blättern, Sternen, Regen und der Sonne. Diese werden aufwendig von Hand gestickt, um die persönliche Geschichte des Herstellers zu erzählen.

Wenn du deine Tasche mit den Mustern Vietnam 5 oder 6 benutzt, denke dabei an die Bilderbuchlandschaften von Sapa & Lai Chau, wo jeder Teil des Stoffes angebaut, gewebt, gefärbt, genäht, gebatikt und komplett von Hand bestickt wurde.

Die Muster Vietnam 3, 11 und 12 und das leuchtende Innenfutter der schwarzen Produkte beziehen wir direkt von unserer Partner-Kunsthandwerkerin Inrahani (kurz „Hani“), die einer kleinen Minderheit im Süden Vietnams, den Cham, angehört.

Inrahani produziert mehr als nur Textilien, es sind kleine „Bücher im Stoff“. Die Designs in den Stoffen erzählen alte, überlieferte Geschichten mit Motiven, die nach Gegenständen des alltäglichen Lebens benannt sind, wie z.B. „Gurke“ oder „Hundefuß“.

Schon frühe chinesische Quellen berichten davon, dass die Cham sowohl Baumwoll- als auch Seidenstoffe webten und dabei verschiedene Farben und Muster einarbeiteten. Cham-Weber wussten, wie man Goldfäden in Kette und Schuss einarbeitet, so dass ein unterschiedliches Muster auf beiden Seiten der Textilien entsteht. Und sie bestickten komplizierte Muster schillernd und luxuriös mit Gold, Silber, Perlen und Edelsteinen.

Während seines Aufenthaltes vor Ort sah Ethnotek-Gründer Jake Orak jedoch verkümmerte Webstühle, die ungenutzt in den Vorgärten der Häuser standen. Da fast alle Bewohner im arbeitsfähigen Alter ihre Dörfer verlassen, bleiben nur Kinder und alte Menschen zurück. Es gab einfach niemanden mehr, der das Weberhandwerk weiterführen konnte.

Inrahani hat den Verfall dieser Tradition miterlebt: „Als ich noch ein Mädchen war, haben fast alle Familien bis in den Abend hinein gewebt. Aber viele haben das Dorf verlassen. Man konnte in der Fabrik arbeiten, ein Verkäufer werden oder körperliche Arbeit verrichten, wie Kaffee oder Cashewnüsse ernten, und mehr Geld verdienen. Es blieben nur die Alten und Schwachen zurück, um sich um die Kinder und ihr Zuhause zu kümmern. Man benutzte die Webstühle sogar als Feuerholz.“

Inrahani machte es sich zur Aufgabe, in ihrem Dorf die Kunst des Webens wiederzubeleben. „Es war fast alles verloren, vielleicht war noch 10% übrig. Aber ich wusste, dass, wenn wir die Weber zurückriefen, sie mit Freude wieder in ihre Heimat kommen würden. Sogar wenn sie nur 3 Millionen vietnamesische Dollar (ca. 125 Euro) im Dorf statt der 4 Millionen (ca.165 Euro), die sie in der Stadt verdienen könnten, ausgezahlt bekämen, würden sie wieder zurückkommen.“

Auch ihr Sohn Inrajaka traf die ungewöhnliche Entscheidung, eine erfolgversprechende Zukunft aufzugeben und aus Saigon wieder in sein kleines Heimatdorf zurückzugehen und sich ein einfaches Leben aufzubauen. „Egal wo ich lebte, irgendwie zog es mich immer zurück. Jedes Mal, wenn ich zurückging und mir Cham-Kleidung anzog, fühlte es sich einfach an, als wenn ich wieder ich selber wäre. Die Nächte im Mondschein, der weite offene Himmel, die Gerüche, die Leute. Ich fühlte, sich hier mein Leben aufzubauen, ist der beste Weg, meine Kultur zu bewahren.“

1990 begann Hani mit einer kleinen Unternehmung, indem sie gewebte Handarbeiten und Souvenirs in Saigon verkaufte. In den folgenden Jahren etablierte sie sich als das Gesicht der Webkunst der Cham. Sie gewann sogar einen Preis als größter Cham-Textilhersteller. Ihr Erfolg erlaubte es ihr, die Kunst in ihrem Dorf wiederzubeleben und die Zusammenarbeit mit Ethnotek war dabei eine große Unterstützung. „Viele Leute haben geredet, aber mein amerikanischer Freund (gemeint ist Jake Orak) war der Einzige, der auch Taten folgen ließ. Er bezahlt uns 50% im Voraus, was es uns ermöglicht, die Rohstoffe einzukaufen. Er hat ein echtes Interesse daran, unserer Gemeinschaft zu helfen.“

Hani nutzt ihren Erfolg dazu, die Gemeinden in den Cham Dörfern zu unterstützen. Ihr Workshop (Atelier) dient gleichzeitig als eine Art Museum und Bibliothek. Hier werden alte Cham Artefakte ausgestellt und Bücher mit alten Schriften der Cham verwahrt. Ihr Traum ist es, eine Vorschule zu errichten, in der die Kinder etwas über die Kultur der Cham lernen können. Sie möchte außerdem ein traditionelles Cham Haus bauen, damit Besucher Einblicke in das Familienleben der Cham erleben können. Ein weiteres Anliegen ist es, alle ursprünglichen 30 Webmotive der Cham wiederzubeleben. „Rot mit Silber oder Gold-Muster für die Männer, Dunkelgrün und andere dunkle Farben für die Frauen". Die Farben und Muster zeigen den Stand des Trägers. Die Muster werden von unseren Priestern getragen, die mit Gott sprechen. Sie werden von unseren Müttern und Vätern getragen, wenn diese von uns gehen. Wie könnten wir diese Tradition aussterben lassen? Wir haben zwar immer noch unsere Cham-Türme, aber das sind historische Artefakte. Ich möchte aber auch dafür sorgen, dass unsere Kultur überlebt – unser Essen, unsere Kunst, unsere Art zu leben.“

Die Minderheiten in Vietnam haben eines gemeinsam: Sie werden entweder an den Rand gedrängt oder zu lebendigen Ausstellungsstücken degradiert. Der sogenannte Ethnozid stellt eine ernsthafte Gefahr für diese Volksgruppen dar, da es an Unterstützung und Verständnis für die Bedeutung ihrer kulturellen Praktiken mangelt.

Die Cham unterscheiden sich insofern von anderen Minderheiten in Vietnam, dass sie mit ethnischen Vietnamesen gemischt und nicht geographisch isoliert wie die Bergstämme im Norden Vietnams leben. Dennoch sind viele der Cham-Dörfer wirtschaftlich schwach und haben kaum Zugang zu höherer Bildung oder anständiger Arbeit.

„Die meisten jungen Menschen gehen weg, wenn sie können“, sagt Inrajaka. Diese Abwanderung junger Menschen erhöht den Druck auf die Cham, ihre Kultur zu vergessen. „Es gibt viele Cham, die denken, es sei nicht wichtig, ihren Kindern die Cham-Sprache beizubringen. Es sei aus wirtschaftlichen Gründen besser, wenn sie Englisch oder Japanisch lernen. Für uns waren einmal Wissen, Literatur und Musik über alle materiellen Besitztümer erhaben, aber heutzutage geht es nur noch um Autos, große Häuser und Geld", bemerkt Inrajaka wehmütig zum Zustand seiner Kultur.

Finde mehr heraus über die Produktion in Vietnam.

Finde mehr heraus über Ethnotek in den Videos auf YouTube.